«Under the microscope [electron], coronaviruses appear to be covered with pointy spires, giving them the appearance of having a crown or "corona" -- hence the name. Beneath the crown is the outer layer of the virus, which is made up of lipids, or what you and I would call fat.»

There's something in there that doesn't really click my intuition.

Cells are said to be made of cytoplasm (a gel made 80% of water and other stuff floating in it) covered by fatty membranes. Please note the same type of membrane is shared by cells, bacteria and viruses.

It doesn't look to me like they have any mechanical resistance at all. I mean, bubbles of water based gel surrounded by a double molecule layer of fat.

If i didn't know about extracellular matrix which is made of collagen i'd say the body tissues can't even stay together.

Collagen is a protein that forms 30% of our bodies. To have an idea of how strong this stuff, is, enough to say tendons which are terminations of muscles through which they are attached to bones are made of collagen. If you make a fist you can see and feel them above the wrists of your hands.

By contrast "The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many viruses are made of a lipid bilayer, as are the nuclear membrane surrounding the cell nucleus, and other membranes surrounding sub-cellular structures. The lipid bi-layer is the barrier that keeps ions, proteins and other molecules where they are needed and prevents them from diffusing into areas where they should not be."

First. We may note in this definition again viruses are separated from living organisms. Then. This lipid barrier separate the chemicals from inside the cells by those from outside. What's keeping it together is electrical bonds between molecules of lipid barrier mentioned above with absolutely no mechanical resistance. If it wasn't for extracellular matrix, those things would probably burst like a soap bubble and fall apart.

And my thought went of course to types of cells that "live" outside a cellular matrix. First thing that came to mind is red blood cells. So i looked and to my surprise i saw they lack a nucleus. "The cytoplasm of erythrocytes is rich in hemoglobin, an iron-containing biomolecule that can bind oxygen and is responsible for the red color of the cells and the blood. ... The cell membrane is composed of proteins and lipids, and this structure provides properties essential for physiological cell function such as deformability and stability" So the natural question comes to mind. Are they alive? and of course that Quora answer didn't clarify anything. And on a further search i could not find an answer to the question if they use oxygen for themselves. Why should they. They don't need to burn oxygen to keep the temperature constant because rest of the body does that from them. I think the're more like molecular assemblies than living cells. Of course they wear out and "die" after a number of cycles of oxygen and carbon dioxide carrying.

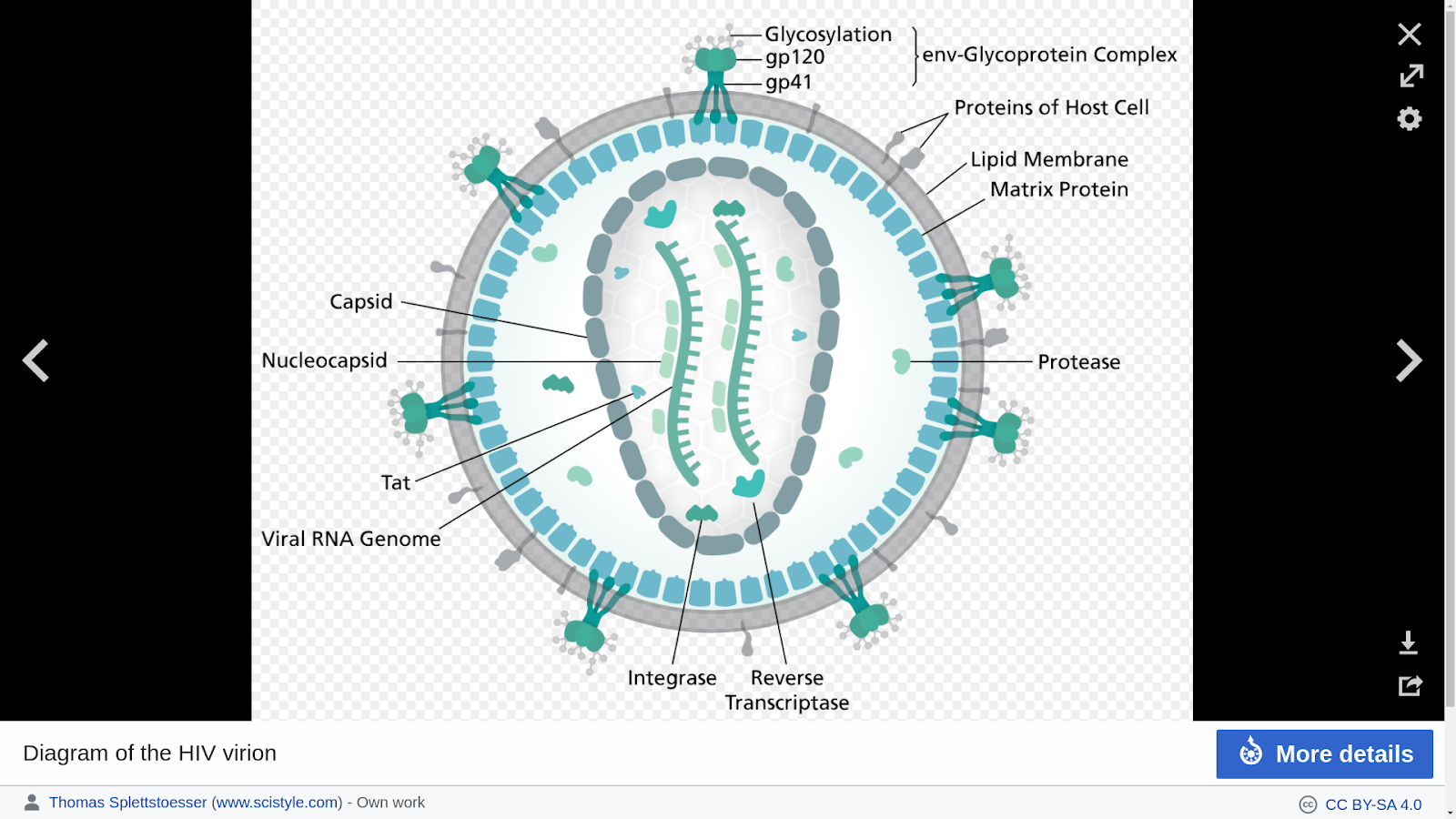

Viruses. Their membrane is again made of a lipid bylayer. They of course don't have a nucleus because the're not cells though inside they have RNA which is part of the nucleus of living, reproducing cells.

Though they are not alive and obviously can't reproduce, once they entered a host cell they can "command" that cell to produce copies of themselves which sometimes are not "exact copies" and thus they... mutate. Some of the mutants will do less, some more than their "parents". The most complicated "component" the host cell needs to "fabricate" using the viral RNA instructions is the spike protein. In fact, the company who mapped this protein and can produce them uses viral RNA (linked later in this post).

I would assume they didn't provide the Jsmol model for the molecule, but here, for comparison, the molecule of HIV spike. If you click on "cartoon" on style for display option you will see the ribbon model. To compare size with lipid by-layer choose ball and stick.

We've saw so far seen the HIV virus looks identical (at least in some media representations) with coronaviruses. Part of the answer is... they are very similar. But the coronavirus misses something. The second membrane layer or the "matrix protein" seen in HIV of which the spikes are seemed to be anchored to.

There are other diagrams of coronaviruses on the web. They all suggest the "envelope" of the virus is made mostly of fat that includes some proteins.

Other, more scholarly articles, trying to suggests that the envelope of such viruses is made more of proteins than lipids. Or even lipids and unevenly distributed protein.

"We present evidence that suggests M can adopt two conformations and that membrane curvature is regulated by one M conformer. Elongated M protein is associated with rigidity, clusters of spikes and a relatively narrow range of membrane curvature. In contrast, compact M protein is associated with flexibility and low spike density."

"CoV virions are enveloped and consist of four structural proteins (Figure 1b). The RNA genome is encapsidated by the N proteins into a helical nucleocapsid, surrounded by a lipid envelope. Two major glycoproteins, M protein, which has three transmembrane (TM) domains, and S protein, which has a single TM domain; and minor non-glycosylated E proteins with a single hydrophobic domain, are incorporated into the CoV envelope"

By looking at the section (c) of the image below, i try to imagine what is the role of M (from Membrane) and E (from envelope) proteins in the envelope of the virus. Are they tied together in a structure or just caught loose in the fat (lipid) membrane.

US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health

"However, a recent electron microscopy study did not detect a well-ordered rigid lattice structure in individual virions, showing instead loosely ordered M-M protein networks [101], suggesting that the lattice-like matrix structure formed by M-M interactions might be flexible and unstable, and so that the model might need some modifications."

By looking at the animated image of the bylayer above and that of the spike protein and the two diagrams from Wikipedia here comes my question. How the gigantic spikes molecule hold onto the loose layer of thin fat (after neglecting the more obvious question that is how corona viruses which are basically a round bubble of fat with RNA inside and spikes outside hold themselves together inside blood). Can't figure yet the size of this protein but is should be certainly 100 times bigger than the two layers of fat acids figured above. Each straight portion of those "ribbons" below is probably as long as half of the thickness of the membrane.

So imagine that. A nanometric blob of fat with some genetic material inside flowing in the air from a sick person nearby getting into your lungs and attacking your cell. That is if your lungs' cilia and mucus don't eliminated them in your esophagus.

But what type of cells this "viruses" "attack" or "attach to"?

«"We then analyzed a total of nearly 60,000 cells to determine whether they activated the gene for the receptor and potential cofactors, thus in principle allowing them to be infected by the coronavirus," reports Soeren Lukassen, one of the lead authors of the study now being published in The EMBO Journal. "We only found the gene transcripts for ACE2 and for the cofactor TMPRSS2 in very few cells, and only in very small numbers." Lukassen and his four co-lead authors Robert Lorenz Chua, Timo Trefzer, Nicolas C. Kahn and Marc A. Schneider discovered that certain progenitor cells in the bronchi are mainly responsible for producing the coronavirus receptors. These progenitor cells normally develop into respiratory tract cells lined with hair-like projections called cilia that sweep mucus and bacteria out of the lungs. Lukassen and his four co-lead authors Robert Lorenz Chua, Timo Trefzer, Nicolas C. Kahn and Marc A. Schneider discovered that certain progenitor cells in the bronchi are mainly responsible for producing the coronavirus receptors. These progenitor cells normally develop into respiratory tract cells lined with hair-like projections called cilia that sweep mucus and bacteria out of the lungs."»

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/04/200407131453.htm

But i bet no "virus" is going to attack you if those types of tissues wouldn't be already damaged. As i said above, most of your body's cells are protected by the strong collagen extracellular matrix through which a fat cover virus cannot possibly get through.

Pollutants, of which smoke is one of the worse factors. Smoke is a very complex compound of air born breathable substances of which the worse by far are heavy metals in ash, which can mutate bacteria creating unknown strain to your immune system, and also damage your respiratory tract lining cells.

In fact, the masks people are wearing to protect themselves from "virus" in fact protect them from the pollutants that may damage their respiratory tracts enough to make them vulnerable for infections because viruses are so small they will pass through most filters, not talking about masks.

As for the vaccine:

"The molecule the team produced – and for which they obtained a structure – represents only the extracellular portion of the spike protein, but is enough to elicit an immune response in patients."

And another question that becomes obvious after all this presentation. Can current HIV medicines be effective against coronavirus, since they are so similar?

"There are many newspaper articles citing effectiveness of anti-HIV drugs: ritonavir, lopinavir, either alone or in combination with oseltamivir, remdesivir, and chloroquine; and among these, ritonavir, remdesivir, and chloroquine showed efficacy at cellular level"

And since i put the two diagrams together to show the similarities with HIV virus, i started asking myself. How come they got flu vaccines which target the spikes ("the stems of the lollipop"), for so long and they don't have one for HIV.

"Doing that would require changing how the vaccine attacks the flu virus, which is shaped like a sphere with lollipops protruding from it. Vaccines so far have targeted the candy at the end of the lollipop, which changes every year."

The answer lies somewhere within the amount of money the drug companies get from insurance companies for a long life time supply of expensive antiviral drugs instead of a one time vaccine.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Friendly comments welcome

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.